Killing two birds with one stone

The Swedish have stirred up a mild flurry of press coverage with the disclosure that Tamiflu does not break down in conventional wastewater treatment systems. The Bloomberg news story says:

Tamiflu in Urine, Water May Fan Resistant Flu Virus, Study Says

Oct. 3 (Bloomberg) -- Roche Holding AG's Tamiflu persists in waste water, which may make the drug a less effective weapon in an influenza pandemic, Swedish researchers said.

Oct. 3 (Bloomberg) -- Roche Holding AG's Tamiflu persists in waste water, which may make the drug a less effective weapon in an influenza pandemic, Swedish researchers said.

The medicine's active ingredient, oseltamivir carboxylate, is excreted in the urine and feces of those taking it. Scientists at Sweden's Umea University found the drug isn't removed or degraded in normal sewage treatment, and its presence in waterways may allow flu-carrying birds to ingest it and incubate resistant viruses.

``That this substance is so difficult to break down means that it goes right through sewage treatment and out into surrounding waters,'' said Jerker Fick, a chemist at Umea University and leader of the study, in a statement yesterday distributed by EurekAlert, a Web-based science news service.

The findings add to concern about the availability of effective medicines in the event of a pandemic sparked by bird flu. Strains either resistant or less sensitive to Tamiflu have been linked to the deaths of at least five people in Vietnam and Egypt. A separate study found Tamiflu may be becoming a weaker weapon against the H5N1 avian flu strain in Indonesia, where the virus has killed the most people.

The spread of H5N1 in late 2003 has put the world closer to a flu pandemic than at any time since 1968, when the last of the previous century's three major outbreaks occurred, according to the World Health Organization. The virus has killed 201 of the 329 people it's known to have infected, the Geneva-based agency said yesterday.

Use With Care

``Antiviral medicines such as Tamiflu must be used with care and only when the medical situation justifies it,'' said Bjorn Olsen, professor of infectious diseases at Uppsala University and the University of Kalmar, in the statement. ``Otherwise there is a risk that they will be ineffective when most needed.''

Scientists say waterfowl, including ducks, are the natural hosts of avian flu. These birds often forage for food in water near sewage outlets. It's possible they might encounter oseltamivir in concentrations high enough to develop resistance in the viruses they carry, the Swedish scientists said in their study, which is to be published in the journal PLoS ONE.

``The biggest threat is that resistance will become common among low pathogenic influenza viruses carried by wild ducks,'' Olsen said. These viruses could then recombine with others that make humans sick to create new ones resistant to the drugs currently available, he said.

Excreted Tamiflu

Millions of doses of Tamiflu have been stockpiled by governments and WHO to treat and prevent flu infections caused by a pandemic. WHO recommends that people infected by avian flu who are older than 1 year receive a five-day course of 750 milligrams of the medicine. The same quantity would be needed for a 10-day course aimed at preventing infection, which could be extended for several weeks until there is no further risk.

As much as 80 percent of the Tamiflu taken in each dose is excreted in its active form in urine and feces and the drug could potentially be ``maintained in rivers receiving treated wastewater,'' researchers from the U.K.'s Centre for Ecology and Hydrology said in a January study.

The potential for resistant strains to emerge this way is greatest in Southeast Asia, ``where humans and waterfowl frequently come into close direct or indirect contact, and where significant Tamiflu deployment is envisaged,'' the study's authors said.

They recommended developing methods to minimize the release of the active Tamiflu ingredient into the waste stream, ``such as biological and chemical pre-treatment in toilets, which could eliminate much of the `downstream' risk.''

Adding to the story, from Reuters:

"Use of Tamiflu is low in most countries, but there are some exceptions such as Japan where a third of all influenza patients are treated with Tamiflu," Jerker Fick, a researcher at Umea University who led the study, said in a statement.

From the AFP wire service story:

Scientists led by Jerker Fick, a chemist at Umea University, tested the survivability of the Tamiflu molecule in water drawn from three phases in a typical sewage system.

The first was raw sewage water; the second was water that had been filtered and treated with chemicals; the third was water from "activated sludge," in which microbes are used to digest waste material.

By the way, the photo at the top of this blog entry is from Konanchubu Wastewater Treatment Plant on Lake Biwa in Shiga Prefecture, Japan. According to http://www.sewerhistory.org/articles/whregion/japan_waj01/index.htm , advanced treatment is used to meet environmental standards for the water quality preservation of this and other designated lakes. The source is the best-selling report Making Great Breakthroughs - All about the Sewage Works in Japan (Japan Sewage Works Association: Tokyo, ca. 2002), pp. 1-56. I know, I know, you've read this cover-to-cover, but I had to include it anyway.

Okay, add Tamiflu to the list of medications you should never dump down the toilet. As we know, environmentalists have been pleading with consumers for years not to dump expired medicine down the crapper, because many of these compounds simply do not break down in the treatment process. Scientists hold the practice of flushing old medicine as being at least partially responsible for the rise in drug-resistant germs. Now we know that Tamiflu, like other medications, takes a licking and keeps on ticking.

What this study also did, by proxy, is help confirm a suspicion that we can adapt an old World War II medical trick for use in a pandemic. This is old news, but it bears repeating. During WWII, medics and corpsmen learned that penicillin use could be extended with the addition of a simple drug -- probenecid. Probenecid slows down the kidneys' natural desire to flush substances quickly. The effect is to double the ability of a drug to perform its desired function. The bottom line effect in wartime was to effectively double the available supply of penicillin. What a clever innovation!

Roche itself has experimented with the concept, as outlined by Dr. Michael Greger in his excellent book Bird Flu: A Virus of Our Own Hatching. Quoting from Dr. Greger's Website:

Roche found that probenicid doubled the time that Tamiflu spent circulating in the human bloodstream, effectively halving the dose necessary to treat someone with the flu. Since probenicid is relatively safe, cheap, and plentiful, joint administration could double the number of people treated by current global Tamiflu stores. “This is wonderful,” exclaimed David Fedson, former medical director of French vaccine giant Aventis Pasteur. “It is extremely important for global public health because it implies that the stockpiles now being ordered by more than 40 countries could be extended, perhaps in dramatic fashion.”2495

Of course, Roche probably does not like the idea of halving the necessary stockpile of Tamiflu! That is quite understandable. But by dispensing and co-administering probenecid at the same time as Tamiflu, you could actually double the number of courses of the antiviral overnight. This has got to be communicated to state governments as a way to heavily leverage the available stockpile of Tamiflu in times of pandemic -- or even severe epidemics, such as we saw/are seeing in Australia.

As we all know, the jury is still out on whether or not Tamiflu will be effective against the next pandemic strain of influenza. We also know the only common denominator among H5N1 human survivors is the administration of Tamiflu. So we can at least hope the antiviral will have some modicum of effectiveness, should H5N1 go pandemic. It is the only pharmaceutical arrow we have in the quiver!

A portion of Roche's study of the use of probenecid in 2002 comes from the blogsite Smart Economy, and the story can be found at: http://smarteconomy.typepad.com/smart_economy/2005/11/smart_wartime_t.html . In part, it says:

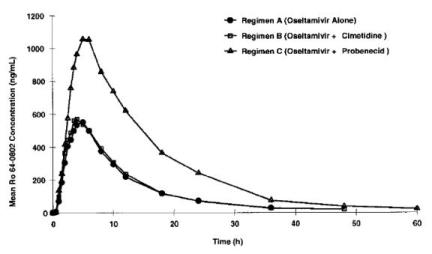

Tamiflu, like penicillin, is actively secreted by the kidneys, and that the process is inhibited by probenecid. "Giving the flu drug together with probenecid doubles the time that Tamiflu's active ingredient stays in the blood, doubles its maximum blood concentration, and multiplies 2.5-fold the patient's total exposure to the drug (see graph, and G. Hill et al. Drug Metab. Dispos. 30, 13-19; 2002)"

Tamiflu, like penicillin, is actively secreted by the kidneys, and that the process is inhibited by probenecid. "Giving the flu drug together with probenecid doubles the time that Tamiflu's active ingredient stays in the blood, doubles its maximum blood concentration, and multiplies 2.5-fold the patient's total exposure to the drug (see graph, and G. Hill et al. Drug Metab. Dispos. 30, 13-19; 2002)"

So the use of probenecid alongside Tamiflu will improve the effectiveness of the capsule by 2.5 times!

Now let's address the issue of the effect of probenecid on the groundwater and wastewater. This abstract is from the Website bionewsonline.com, specifically at: http://www.bionewsonline.com/f/1/bioremediation_a.htm :

Acta Microbiol Pol, 2003, 52(1), 5 - 13

Overuse of high stability antibiotics and its consequences in public and environmental health; Zdziarski P et al.; In this paper the ecological aspects of widespread antibiotic consumption are described . Many practitioners, veterinarians, breeders, farmers and analysts work on the assumption that a antibiotics undergo spontaneous degradation . It is well documented that the indiscriminate use of antibiotics has led to the water contamination, selection and dissemination of antibiotic-resistant organisms, alteration of fragile ecology of the microbial ecosystems . The damages caused by the overuse of antibiotics include hospital, waterborne and foodborne infections by resistant bacteria, enteropathy (irritable bowel syndrome, antibiotic-associated diarrhea etc.), drug hypersensitivity, biosphere alteration, human and animal growth promotion, destruction of fragile interspecific competition in microbial ecosystems etc . The consequences of heavy antibiotic use for public and environmental health are difficult to assess: utilization of antibiotics from the environment and reduction of irrational use is the highest priority issue . This purpose may be accomplished by bioremediation, use of probenecid for antibiotic dosage reduction and by adoption of hospital infections methodology for control resistance in natural ecosystems.

From Wikipedia:

Bioremediation can be defined as any process that uses microorganisms, fungi, green plants or their enzymes to return the environment altered by contaminants to its original condition. Bioremediation may be employed to attack specific soil contaminants, such as degradation of chlorinated hydrocarbons by bacteria. An example of a more general approach is the cleanup of oil spills by the addition of nitrate and/or sulfate fertilisers to facilitate the decomposition of crude oil by indigenous or exogenous bacteria.

But hey, Wikipedia also says bioremediation was invented by Al Gore, so what do they know? Just kidding on that one.

So let's get jiggy and begin stockpiling probenecid. The use of probenecid alongside Tamiflu, accompanied by a scientific study, would also tell us if the increased time in the human body before peeing it out would reduce the amount of Tamiflu to go into the groundwater, lakes and rivers. It may also tell us if the effective increased dosage (2.5 times!) of each pill might beat back the rapid escalation of virus in human lung cells (remember that Tamiflu is a neuraminidase inhibitor).

While we are at it, let's look at Japan and see if, indeed, we can make a correlation between the (over)prescription of Tamiflu, the amount of active Tamiflu found in treated wastewater, and the Tamiflu resistance now seen in 3% of Japanese Influenza B strains. Again, from the AFP story:

The study, published online on Wednesday by the open-access Public Library of Science (PLoS), pointed the finger at Japan.

It quoted figures from Swiss maker Roche, which estimated that in the 2004-5 influenza season, 16 million Japanese fell ill with flu, of whom six million received Tamiflu.

At such dosages, the amount of Tamiflu released into the Japanese environment is roughly equivalent to what is predicted in areas where the drug would be widely used in a pandemic.

Coincidentally, "Japan also has a high rate of emerging resistance to Tamiflu," the paper said. A 2004 study published in The Lancet found that among a small group of infected Japanese children, 18 percent had a mutated form of the virus that made these patients between 300 and 100,000 times more resistant to Tamiflu.

And throw old medicines away: Don't flush!

References (1)

-

Response: soilsoil level items

Response: soilsoil level items

Reader Comments (1)

In New Zealand doctors surgeries and pharmacies encourage people to hand in unused medications so they can be disposed of safely.

Don't dump them. Don't flush them. Hand them in.